Visualizing Weather, Making a Weather Picture

©PamelaGL. Heading to Tiniteqilaq through Sermilik Fjord, East Greenland. 15.02.2023

BGAM - AGM

BGKK - KUS

Visualizing Weather - Making a 'Weather Picture'

For helicopter pilots, the difference between the East Coast and the West Coast can be thought of in terms of wind direction and speed. When there are strong winds and perhaps forecasting a low-pressure movement, a pilot with over 2o years of experience flying various helicopters in Greenland may be quite fine taking off in the B212 rather than in the Sikorsky S61. It’s not that the 61 cannot handle turbulence, it’s the 212’s ‘rounded’ body (image above).

Although the 212 is no longer in Air Greenland’s current fleet, it performed several functions from 1980 - 2022. Not least whether it’s the B212 or H155, or AS350, or the S61 or H225, operations are specified for that machine's technology.

The previous post noted that the Neqqerjaaq, strong North North Easterly wind, in Kulusuk has minimal effect in Tasiilaq. Likewise, Kulusuk is bypassed by the Piteraaq. The East Greenlandic, Piteraaq, is acknowledged as a meteorological term. Piteraaq are specific to the weather system here in East Greenland affecting coastal settlements of Tasiilaq and Isortoq. Similar weather phenomena are known in other places in the world with different names such as Mistral or Bora.

As mentioned in the previous post, the pilot analyses the ‘actuals’ in the Terminal Aerodrome Forecast (TAF), and the Aviation Routine Weather Report (METAR), plus en route forecasts, satellite images, and looking up out of the hangar. In the world of electronic weather information, sources are plentiful. A pilot may even take an iPhone picture. This image is not without caution. Because the mechanics of the camera make ‘visible’ what the eye cannot see, the camera optics give a more positive picture. The camera can lie. It can definitely give a more optimistic view.

Pilots tend to not want any surprises airborne when it comes to weather. With all the weather sources available and live heliport cameras, pilots also create their own ‘weather picture’.

There is a mental process here when creating a ‘weather image’. True, the WX provides a pretty good picture of the weather. The importance is to make a weather picture and then visualize it. The other key point here is to do this before taking off. When airborne, it becomes easier to relate what the METAR and TAF reported.

While flying with the H155 and the AS350 helicopter pilots, more posts will try to capture the ‘weather picture’ in various heliports in Greenland. Questions are:

How do pilots build their mental map of the local weather system? Do they make a mental note of visual cues?

Further along, new entries or posts explore the mental weather map during pre-flight analysis that pilots absorb and hopefully, the WX soaks into the long-term memory.

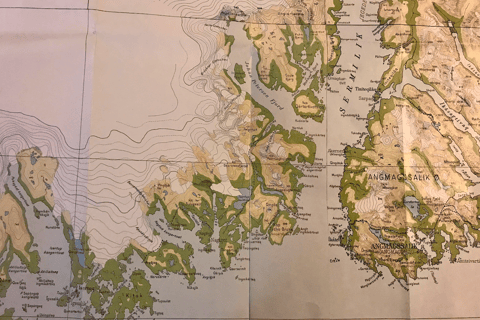

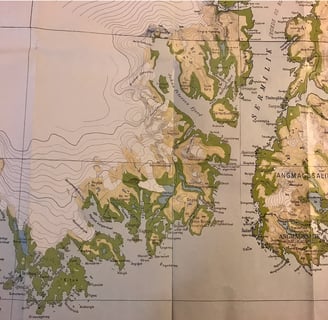

It’s safe to say, when a Piteraaq is forecasted, it is a No Go. The day before, warnings are posted throughout Tasiilaq. It’s recommended to protect windows, fasten things down, and stay inside. If pilots visualize a Piteraaq, they visualize a low-pressure approaching Greenland from the East. There would be no cloud formation. In place is a cold, high pressure that sits on top of the ridge where the inland ice meets the sea about 50km from the coast. As shown on the map above, the ice sheet is steep in the East Coast compared to the West Coast (more in the upcoming post from Uummannaq District).

For the pilot with over 20 years of experience, he had the bigger weather picture of the steep ice sheet in this area. From his experiences, he knows that the wind starts from the top of the ice sheet and as this katabatic wind descends, it intensifies. And when that cold dry air from the ice sheet meets the low pressure from the coast, the pressure gradient tightens, and the wind accelerates. Between the coastal valleys, the wind velocity increases.

A Piteraaq has the potential to reach hurricane speed of 155 knots gusts, average speed of 77 knots. Still, it is difficult to predict the intensity of the wind speed. The Piteraaq’s dominant effect is along the coast and valleys. The settlements of Isortoq and Tasiilaq (Angmassalik) are in its direct line. As it weakens over the sea, Kulusuk will barely notice the Piteraaq.

There is also the bigger weather picture. Greenland’s 44,000 km coastline and 80% of inland ice is the foundation for building a weather picture. Pilots here fly in very distinct atmospheric conditions and are always alert knowing the weather could change rapidly, especially due to: heliports being located near open water (frozen during seasons), VFR night flying (late day flight near darkness during seasons), flying in continuous mountains areas, snow-covered heliports, and flying the coast where alternates are few and far. (Image below, Sermiliqaag heliport feb 2023 before sunset)

Pilots can visualize the katabatic winds flowing down from the inland ice on a weather map. They can visualize the strength of the wind. They also know that the Piteraaq will eventually dissipate.

Experienced pilots would see the WX with a fuller picture. Pilots do this by creating a ‘mental’ picture from the descriptions given in METARs and TAFs. It is however a challenge to put the raw data to form a mental picture. Aviation weather is cryptic and knowing it well is to decode the language.

Take, for instance, a sample of a METAR, from NorthAviMet.com of Kulusuk.

SOON BECMG SCT/BKN SC BASE 1200-2500 FT ELSE SKC OR ALMOST.

While a rough picture can be created, the details are missing. The key here is to know that there will be a development and to keep checking.

For those flying in Greenland long enough, the saying goes,

‘Even though it might look like blue skies with an opening, just wait and ..... never take off on the first clearing’.

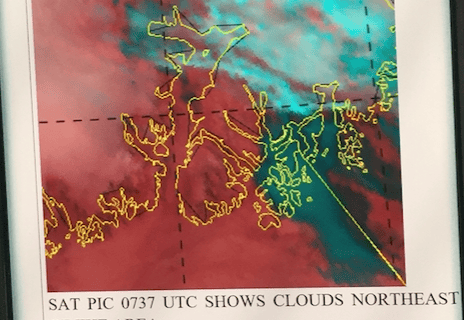

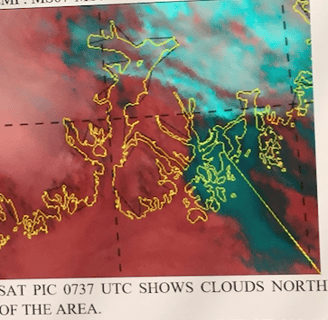

On that same weather report from NorthAviMet.com, there was a satellite image (below). In this image, we see cloud cover and possibly a degree of thickness, but nothing of the ceiling or cloud bases. Although technology is ever increasing and experts can tell the top heights. the usefulness of Sat images is that they add to the pilot’s weather picture. Images may very well confirm what pilots read from the WX. If the WX seems not to match the image, then pilots dig deeper and check when the Sat image was taken compared to the report.

The important point with Sat images is that although it is a past image, it assist in seeing the direction of weather movement, trends, and timing. The bigger weather picture of Greenland on the East Coast is the cloud movement, high and low clouds, fog dissipation, fronts moving in, pressure systems, and the overall winds flowing down from the inland ice affecting the local weather system.