Flying into Weather in Greenland

©Pamela. Ferry flight starting in Upernavik District heading south with sunrise towards Svartenhuk 16Oct.2021

Introduction Post 4 May 2024. East Greenland

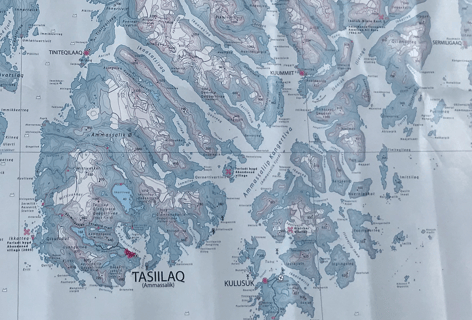

Lat 65.574, lon -37.124, gravel Airport, BGKK - KUS Kulusuk

Lat 65.612, lon -37.618, Heliport, BGAM - AGM Tasiilaq (hangar above)

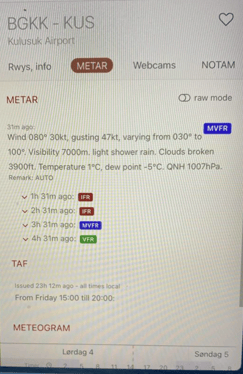

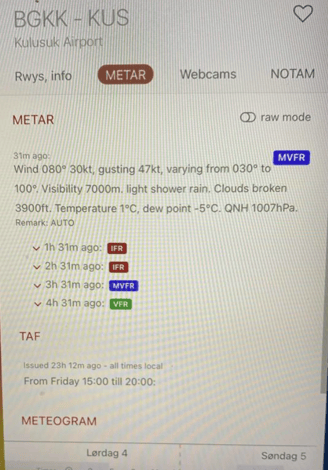

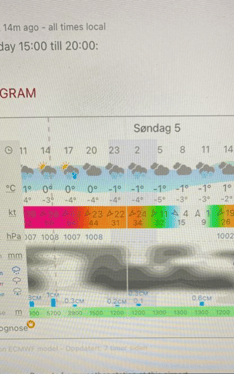

When the pilot wakes up in the morning, he/she goes down to the hangar at the settlement base, pours a cup of coffee, and gathers the weather data. The WX or weather data includes the METAR, the TAF, an en route forecast and other sequences of reports from various weather services prepared by ICAO-approved (Int'l Civil Aviation Org.) sources, in addition to other reports. However, these sources are not limited to what was just stated.

In Greenland, weather sources are walking out of the hangar and/or making a personal phone call to the MET office. Some pilots even call the local food store in the settlement where the pilot is flying to, asking specific questions: “Do you see the mountain ahead, Do you see the island in front, Do you see the tops of mountains, Do you see the other side of the fjord?”. This is getting the actual weather.

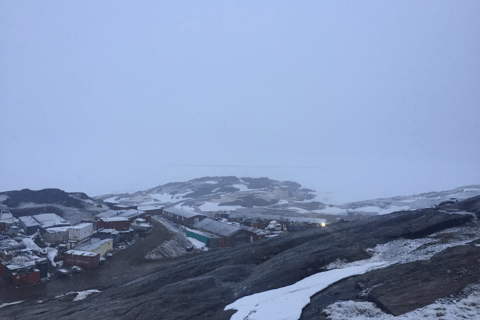

Flying in Greenland arguably is known as flying into weather.

This type of flying is VFR which refers to Visual Flight Rules where the terrain is visual at all times.

Pilots rely on ground support and the mechanic to have the aircraft prepared before the first flight. Pilots know their machine. Flight plans have been inputted on the iPad and the helicopter itself is ready to be taken out of the hangar to be fuelled.

But the weather…………………?

This is what makes VFR flying challenging and when the weather is not CAVOK (ceiling and visibility OK, and no significant weather change), it tests the pilot’s ability to make good judgments.

No matter how much pilots know meteorology, they always like to get as many sources as possible. Especially in Greenland when weather is so localized, wind gusts reaching over 50 knots in one fjord will not affect the next fjord.

On Saturday 4 May, DMI (Danish Meteorological Institute) issued a warning of NNE winds between 28/33 knots in Kulusuk Airport KUS, where aircraft with STOL (short take-off and land) requirements can take off and land. KUS is where the De Havilland Canada DHC, Dash 8 of Air Greenland and Icelandair can land. 12 NM West of KUS is Tasiilaq AGM. This is where there is a hangar for the helicopter.

Weather in Tasiilaq may be flyable, while in Kulusuk it is a No Go. Locally, this weather phenomenon of strong North North Easterly winds is known as Neqqerjaaq in East Greenlandic.

The other weather phenomenon, Piteraaq, are katabatic winds flowing down from the inland ice that affects Tasiilaq. See other posts for more on Piteraaq.

In this weather phenomenon, there is little hesitation from flight operations to cancel the settlement flights via the H155 (EC155) helicopter and the Nuuk to Kulusuk flight via the Dash 8.

Somedays, the question to take off will take more analysis. For pilots, the questions are:

Go or No Go, What will I do with all this weather data, Is there a route above or below or through the weather, Do I go around the weather, Will it clear near approach, Do I do a short reconnaissance of the coast, Do I delay for two hours or Go when there is a weather window?

There are days when the decision-making is easy. However, every so often, depending on the season, the month, and the time of the day — something beyond the pilot’s eyes worries him or her. How well pilots deal with these decision-making moments is dependent on his or her experience flying in that local weather system.

Pilots who know their machine also determines how they deal with difficult weather decisions. One experienced Bell B212 Pilot knew his machine well. True, the flight manual sets limitations for what is safe for the machine. Manufacturers have limitations for safety. Not least, the more the pilot gains experience, his/her own personal 'limits' shift which guides them in their flying.

Case in point:

There was a MEDEVAC to be pick up by Icelandair in KUS. At that time, Icelandair handled MEDEVACs for East Greenland. The WX forecasted a Neqqerjaaq. The pilot was in AGM. He got the actuals, the METAR, TAF, and other weather services like Asiaq and Windy. He even called Kulusuk Tower to gauge the wind direction of both ends of the runway. Threshold 29 reported gusts up to 57 knots and threshold 11, 12 knots. (image below of KUS tower and gravel runway).

Did he think through this? - YES.

As an experienced pilot with over 8000 hours at that time, he had a solid understanding of weather in Greenland. He felt the need to explore this. Like most experienced pilots, when they do have the knowledge and experience, they use all the resources to make a good decision. They would also say, it is about one's own confidence. When the experienced pilot made his decision, his confidence was higher.

As he said, “Live and learn. Day 1 to year 35, I built my experience on what I’ve done and what can be done or how to get the best result. If I can do the job and defend it, yes I will do the job.”

On that day, he knew how the Neqqerjaaq behaved, and he knew his machine.

It was a Go. He flew over 11 knowing the 57 knots gust was over 29 and he was able to defend the outcome of the flight.

The question then becomes how do you gain self-assurance or self-confidence? This is a question worth further discussion in upcoming posts. By having flight discipline, pilots strive to become better. As flight discipline is the cornerstone of airmanship, the upcoming posts will bring in what is flight discipline and how pilots understand this term.

Part of this term speaks to the adherence to OPS, REGs, Organizational, and simple common sense. Not least, flight discipline does not mean a lack of skill, proficiency, or knowledge of the flight environment. Yes, the pilot does need to know the machine to safely fly it. A slight diversion from OPS procedures, such as in commercial aviation, could have devastating consequences.

Perhaps you have heard the saying,

‘There are old pilots, and there are bold pilots, but there are NO OLD BOLD pilots’.

Daring pilots tend to become an example of a safety report or have nine lives. Too reserved pilots tend to not make use of the utility of the helicopter and the machine flies the pilot. Pilots will say that it is a process of knowing themselves. With experience, they know when to improve their flight skills because after all, knowing oneself allows for building on skills and proficiency. At the same time self-conscious enough to not push it too far. The difficult part is not to be too self-confident. We’ve all heard of cocky helicopter pilots.

When it comes to weather decisions, the less experience a pilot has, the more difficult it can be. Pilots though, talk about this ‘gut feeling’. Although it could be described as a struggle between trying to make a good call and uneasiness, the body is processing something that perhaps the mind is not able to.

Having a ‘gut feeling’ develops from past experiences from the last time the pilot diverted a what could have been. It comes from comparing what has happened before and not being satisfied with the result.

Or if there is a significant other waiting for them at home. Or if the body is reacting restlessly. These things are weighed in the decision-making process.

The saying, 'If there is doubt, there is no doubt.' This can also be a ‘gut feeling’.

Pilots often will look again at their weather sources, walk around and think. At times, pilots in single-pilot operations might say to themselves, ‘I wish I could go over the weather data with another experienced pilot.’

If possible, he or she could talk it over with the level-headed mechanic who most likely will have experience with the local weather if the mechanic is from Greenland.

Building up experiences flying in Greenland really makes a difference, especially in making good weather decisions.