pilotgreenland

Before the Southeasterly Winds

It's late April. Spring arrives on the East Coast of Greenland. The sea ice in the bay is frozen still, but the Sun moves in. Its warmth heats the waters along the coastline. Similar to other regions of the north, in Greenland, the Sun's appearance is uneven. Depending on the latitude, in mid-winter, the Sun stays for short periods or not at all. Yet in mid-summer, it anchors to the sky, lingering past midnight.

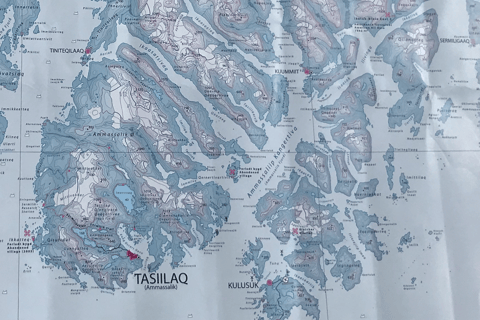

Here, Tasiilaq is below the Arctic Circle and has a local weather system unique to the East Coast. I was informed by Pilot RP that "If you look on the map of this area, the area curves with the coast. In some way, it looks like the weather gets stuck here. The winds can blow parallel to the coast, but then along the coast, it changes directions. The air movement upwards creates a lot of weather in this area."

Not visible on the map above, the difference between high and low winds and the resulting weather is experienced by pilots taking off from Tasiilaq to the settlement nearest to the Inland Ice, Isortoq - in the Spring when the East Coast sees a lot of fog. Pilots become more observant when there is a decrease in wind intensity and low visibility, particularly near open or ice-chock waters; flights late in the day toward darkness; flights surrounded by mountainous areas; flights to an area where there is lots of moisture in the air from the broken sea ice - all this creates fog conditions. And in the East Coast, the possibility of fog is all year round. The other pilot I met up with on duty in Tasiilaq, Pilot JP, had something to say about this:

"Sometimes the weather report from the nearest airport (KUS), in this case 12 nautical miles away, forecasts something that does not reflect what is the actual weather on the ground. From Kulusuk (KUS), the forecast noted an opening of some hours during the day, but the fog, according to the report, the fog will never leave. But, here, some local factors can shift the current conditions. Depending on the wind direction, if it comes from a direction that does not move the fog, the fog gets stuck in the bay. If there's a northerly wind down from the Inland, depending on how strong, for instance. I had a gut feeling this was a local thing. If there is a southeasterly wind, this can push the fog.

I looked at the temperature and the moisture in the air. Because of the Sun's warmth over the island and the cold surface of the sea ice, when the warm air moves from the cold surface and the air reaches its saturated point, it creates fog, low clouds, and/or precipitation. When the fog is over the sea ice and the Sun is high over the island, like it was, this means I can fly over the fog patches the whole day and not have any problems."

Above is the descent from Inland Ice taken in April, where ski expeditions cross the Inland from West to East begin their descent. Isortoq lies at the bottom to the left.

Pilots often talk about this ‘gut feeling.' Although it could be described as a struggle between trying to make a good call and uneasiness, the body is processing something an indirect feeling, perhpas an implicit feeling. Pilot JP went by his gut feeling, referring to"it's a local thing here." Perhaps having that 'gut feeling' can only be experienced in that moment, in that the experience is felt only when weighing decisions. As these pilots have informed me, having a ‘gut feeling’ develops from experiences from the last time he/she diverted a what could have been. It comes from comparing what has happened before and not being satisfied with the result, which definitely entails a learning process. Implicit things are weighed in the decision-making process. There is a saying pilots often hear 'If there is doubt, there is no doubt.' This can also be a ‘gut feeling.’

Here is a what could have been flying to Isortoq:

"I was flying into Isortoq, the settlement near the Inland Ice. Actually, Isortoq, as the locals tell me, means foggy sea. I didn't expect it. Flying over the long stretches of sea ice, it turned bad. Bad visibility and up ahead was a snow-covered sky - it was a whiteout. I had to return to Tasiilaq."

Pilot HP pauses, possibly thinking about that time. Drinks from his coffee cup, and continues:

"The fog and whiteout conditions come from being close to the Inland Ice and the open water out of Tasiilaq. With the cracks from the sea ice as well as the drift ice, there is always the possibility of fog. In the Spring and Summer months, straight out in the open ocean, with the moisture of cold air moving over warmer water, is a surefire for fog. But again, the fog would build up outside Tasiilaq and drift in over the bay, and with the sea ice being cold, the fog cannot go anywhere, so it sticks in the bay. Unless there's a southeasterly wind.

Winds

Winds over the course of the day often follow a predictable weather pattern, most noticeable during the Summer and over land. At daybreak, calm air surrounds. As the Sun rises, uneven heating occurs over the sea ice and islands on the coast.

It's the wind that moves the air and partly dictates how much visibility is in the air and how much flying is possible - that is, with some local weather knowledge of why the fog sits or when the fog moves. The local weather system, in this chapter, is the winds, the surfaces, and the Inland Ice that tells a weather story.

Before the southeasterly winds, the atmosphere is made of millions of air parcels. Before the YR.app or Windy app or DMI forecasting models, seasoned pilots could see something in the distance or the sky that would give them a weather confidence, for instance, "Wait two hours, it will clear." Perhaps this magical statement can be learned. In this process of gaining experience in learning the local weather, a strategic observation is done in a reconnaissance.

Reconnaissance

During a reconnaissance of an unfamiliar place, from all that is in the environment, the surface doesn't always become obvious. Mediated through the machine's body or airframe, pilots observe the surface of the runway/heliport to minimize the downwash of deflected air. Gibson (1986, p.78) refers to a specific word, "occlusion," and defines an occluded surface as things "out of sight or hidden in view." From Gibson's point of view, when we look out, there are obstructions in our way, an environment 'cluttered' with 'objects,' but it is from the 'point of observation' whether we see the features projected at a point of observation or not see features when the surface does not cast a light on the object. When pilots fly and look out at the cloudless sky, they see no obstruction. Perhaps following along the linear horizon on a Great Circle, the shortest course between two points on the surface of a sphere, frees up the eyes looking out at the open arid sky. Closer to the ground, small particles are hidden or out of sight. So, where does he/she begin to look?

The basic features of the environment that Gibson (1986, p. 240-242) brings to the fore are in the surfaces in the background, edges as contour, and, as mediums such as the air, an event of change, substances that have a core element, and the immateriality and materiality of objects, that possess some affordance to the observer of where to look. Naturally, some light conditions will spread over the surface. However, pilots note light conditions when doing reconnaissance over the Inland, known as flat light, a light condition that offers very little indication of surface angle or slope. Because Gibson (1986, p. 79) terms it so well, and not to be confused with disappearance and appearance, or visible and invisible, he notes a point of observation is "coming out of and coming into sight." The second post in this section, there is an account from the Pilot RP and HP who accounted for what to look for when flying to the Inland Ice. Any reconnaissance also brings to light the drawbacks of affordances of surfaces that are coming in and out of sight.

Ground Reconnaissance

Ground reconnaissance, if unfamiliar to East Greenland, is also to identify the settlements. Surrounding the island of Ammassalik (Angmagssalik and King Oscar Haven), hidden in fjords where sea-ice packs in; somewhere along the coast, in between the Sermilik fjord and Helheim Glacier (one of the largest glaciers that drains into the fjord) and the mountain range north of Tasiilaq, are small settlements of Tiilerilaaq (formerly Tiniteqilaaq), Kuummiut, Kulusuk (formerly Kap Dan), Isortoq, and Sermiligaaq that lie at the base of the fjords. Isortoq is nearest to the Inland Ice; white clouds, white snow, the monochromatic presence of the ice overshadow the terrain near Isortoq. Tasiilaq, with the largest population (around 2000 people) inhabits the bay, and when landing or taking off, the natural thing to do is to follow the curve of the bay. Look north towards the Scoresbysund fjord system, and there lies the settlement furthest northeast, Ittoqqortoormiit (70° 29' N, -21° 58'W), which is considered 'most isolated' perhaps from the rest of Greenland, however, Iceland lies to the East.

Flying in this direction due East, Nuuk was far behind. The travel that began on the West Coast in Nuuk passes over the Inland Ice. So, when the Dash 8 does land on a gravel runway (1199m, 3934ft), it takes little imagination to see East Greenland’s buildup of geological conditions that were shaped 60 million years ago. Much of what is felt on the ground today is mud and gravel. North of Kulusuk, cross-bedded sandstone was deposited by rivers. But the spread over of these sediments was succeeded by finer-grained marine mudstones separated by beds of sandstone. To an un-geological eye, the sediments would only be seen as mud in the warmer months and hardened soil in the colder months.

Runway surface conditions on the East Coast are familiar to pilots. If unfamiliar, Ground Reconnaissance is done prior to departing for both take off and landing. Kulusuk's runway surface can be described as gravel. The gravel, the sandstone, and the marine mudstone pack down is distinct to this runway location, which is surrounded by mountains along the coastline. The American Military found East Greenland rather suitable in its location. It was in the 1950s when they slipped in after the Second World War, building radar stations and the Kulusuk runway. A strategic labor of airport construction in 1956 supported the Distant Early Warning (DEW) line that detected Soviet bombers over the Arctic. 80km away on a glacier, back in July 1942, the US Air Force P-38 Lightning was forced to land after flying for hours on low fuel. Eventually, in 1992, it was recovered, and when rebuilt, it was named 'Glacier Girl.' A small reminder, Greenland's infastructure has been shaped by airports built for Amerian military purposes (Pituffik, before Qaanaq, Kulusuk, Kangerlussuaq, Narsarsuaq) before commercial use. The new airport and runway (since 28 Nov 2024) built in the capitlal of Nuuk begins a new era of Greenland built. As Greenland is under the Realm of Denmark, building of all the other airports were with agreements between Denmark and Greenland.

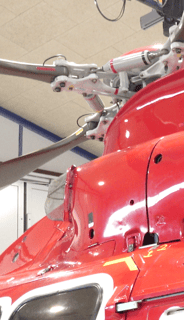

In Kulusuk, although the helicopter does have a landing pad made of stone tiles, to a pilot’s eye, the runway’s gravel surface with all the scattered particles is less favorable to the operating helicopter. Surfaces that are not asphalt affect the air movement. As expected, particles begin to swirl around. To lessen the air movement, for modern helicopters with wheels, a rolling or running technique where there is reduced power to reach transitional lift can minimize the downward force due to the movement of air deflected by the aerodynamics of the rotor blades to produce lift. On the surface, any helicopter seems solid in airframe, materials, and technical specifications. As all machines have their pros and cons, getting to know the machine for its capacities leans on both the pros and cons. For example, the running/rolling technique can minimize downwash, yet when considering power requirements, running/rolling takeoffs are also avoided. In the 3 min video, take a look at the mountains, the runway, the stone tiles helipad - see the surroundings.

Click on the below to see the real flight environment. The instrument is the navigation display.

Click to see the video of the approach to Kulusuk airport and landing on the stone-tiled helipad. Pilots observe their surroundings unique to the East Coast.

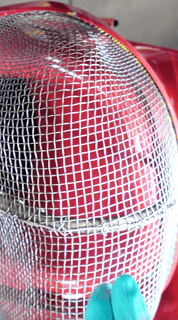

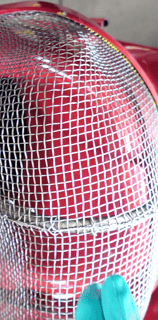

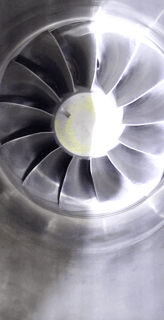

After the last flight on the day's plan, the mechanic on base does the routine maintenance check. I think it's quite interesting to see all the parts that come together once the cowl doors come off. We looked at the engine. An example of 'on the surface things look different' is the engine air-intake cover that covers the air compressor that intakes air into the engine. All engines produce power by breathing in air.

According to the mechanic, "On this machine, there is no particle separation but a mesh cage that covers the engine. It's a direct intake of air. Particles that could go into this compressor do not get sorted out, such as pebbles that could directly go into the engine."

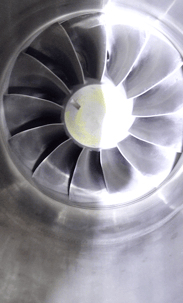

Click on close-up images of the mesh cover, the air compressor blades, the mesh cover close up from another angle, and the machine cover on the machine. When the mechanic takes off the mesh cover, under the cover is the air compressor blades.

On other machines, air that moves in the intake will shoot through the intake, but air flows out again. In a direct air-intake, there is no filtration of particles. On some machines, the air-intake is on the side on top of the roof with an opening where the intake air is filtering in what goes into the engine. As Pilot HP has noted, "Perhaps, the particle separation of air-intake slightly reduces power of the machine, and that's maybe why some machines do not have it."

Pilot OP familiar with both types of machines stated, "Power loss is just slightly, so it’s no problem on a machine with a particle separator, but the machines with no filter that have a direct air inlet, there is no loss of power in that way. But very vulnerable when it comes to dust, sand, stones or icing."

No matter what type of machine, to know the machine you fly is to know if there are any trades offs and the effect of the trade-off, as wells as the regulatory policy that must be adhered to for safety (i.e power requirements and weight). There is always a balance to attain between the flight environment and the machine, whether the effect of the wind, air density and/or dynamic pressure. In this case, between the type of machine and the landing surfaces.

Air Compressor Blades draw in air into the engine, squeezing it, and raising its pressure.

Mesh cover from another angle

See mesh cover above on the helicopter

As the Compression blades are at the heart of a turbine engine, this mesh covers the air compressor blades.

Get in touch